A Physics Lens on Market Fear

In physics, the world is governed by forces—predictable relationships that describe how objects respond to change. One of the most fundamental is Newton’s Second Law: Force = mass × acceleration. It tells us that the impact an object feels is not only a function of the change around it, but also of the object’s own size and exposure to that change. A small shift acting on a light object generates a mild effect; that same shift acting on something larger produces something far more dramatic.

Personal finance isn’t physics, but human behavior often follows laws of its own. Markets move, portfolios fluctuate, and emotions react accordingly. When investors find themselves stressed, fearful, or overwhelmed, it’s usually not because of the market alone. More often, it’s because of a simple financial corollary to Newton’s law:

Fear = market movement × allocation

Why Allocation Changes the Emotional Equation

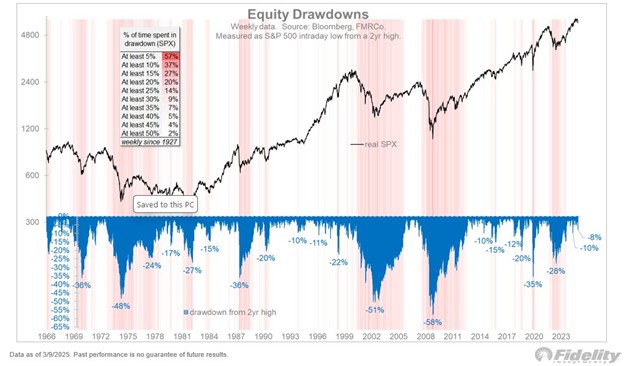

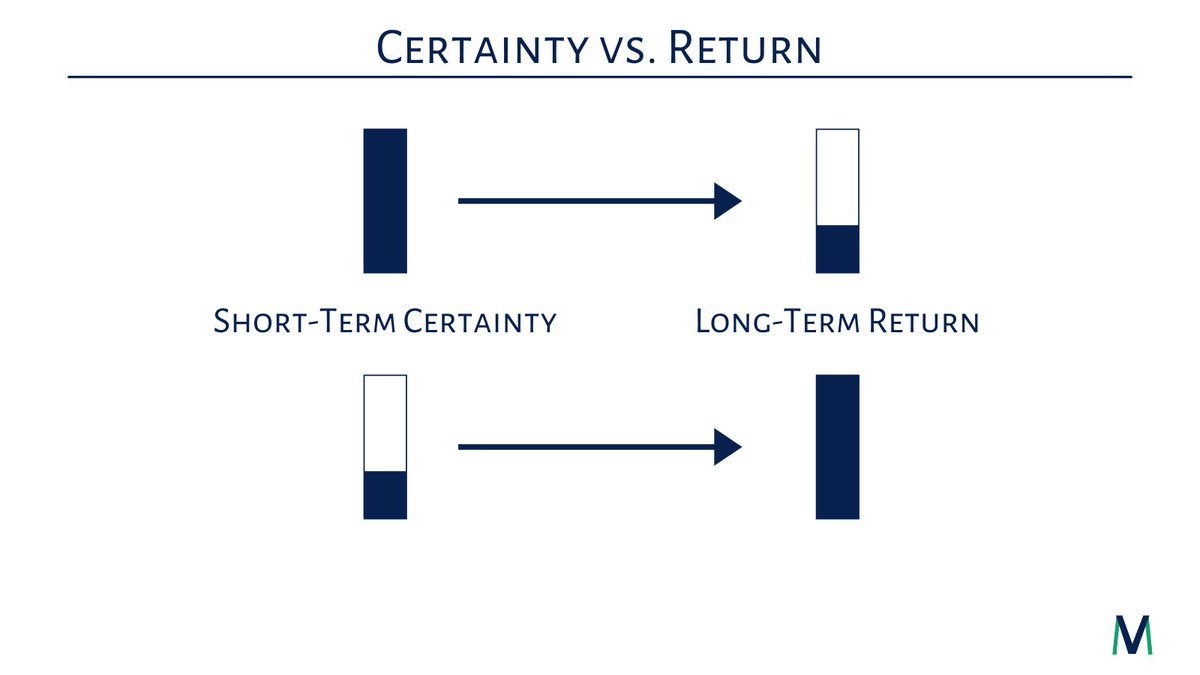

Just as a force increases with mass and acceleration, investor fear rises with the magnitude of their market exposure and the speed of market downturns. A 3% drop in the market feels very different when an investor holds 30% equities versus 90% equities. The same external movement can trigger wildly different internal reactions depending on how heavily someone is allocated—and how quickly markets are shifting beneath them.

This is why sharp downturns cause such widespread panic. It isn’t merely that the market is falling. It’s that the acceleration of those declines magnifies emotional force, especially for investors with heavy concentrations in volatile assets. When the market moves swiftly, and an investor’s allocation is fully exposed to that movement, the resulting psychological “force” can be overwhelming. The outcome is predictable: hurried decisions, reactive portfolio changes, and a heightened risk of permanent loss.

Balanced portfolios exist for precisely this reason. In physics, increasing resistance or distributing mass can help absorb force; in finance, diversification does the same. Bonds, cash reserves and even global diversification each act as buffers—dampening the acceleration of market shocks as they reach the investor and reducing the emotional impact that follows.

A balanced portfolio doesn’t eliminate downturns, nor does it mute volatility entirely. Instead, it moderates the emotional force investors experience. It allows for a steadier hand in the midst of uncertainty. When markets decline rapidly, investors who have diversified allocations feel less psychological whiplash. Their exposure is spread across different types of assets, each reacting differently, each cushioning the impact. Instead of fear being multiplied by both sharp market movement and heavy concentration, the equation becomes more stable, more manageable.

Ultimately, physics reminds us that impact is never just about external conditions—it’s also about our own structure and preparedness. Financial planning works the same way. We cannot stop market accelerations any more than we can stop gravity, but we can design portfolios that absorb these forces rather than amplify them. A balanced allocation is not merely a mathematical choice; it is a psychological safeguard. It gives investors the resilience to withstand downturns, stay disciplined, and remain aligned with their long-term mission—even when the market accelerates in the wrong direction.

In uncertain environments, preparation—not prediction—is what protects us.